Photography is a medium rooted in both observation and expression. To grow as a photographer, especially in today’s fast-paced digital culture, it’s important to look backwards and sideways—to study the work of others. This doesn’t mean copying or imitating; rather, it’s about learning, absorbing, and eventually shaping a visual language that feels uniquely yours.

Learning to See Through Others’ Eyes

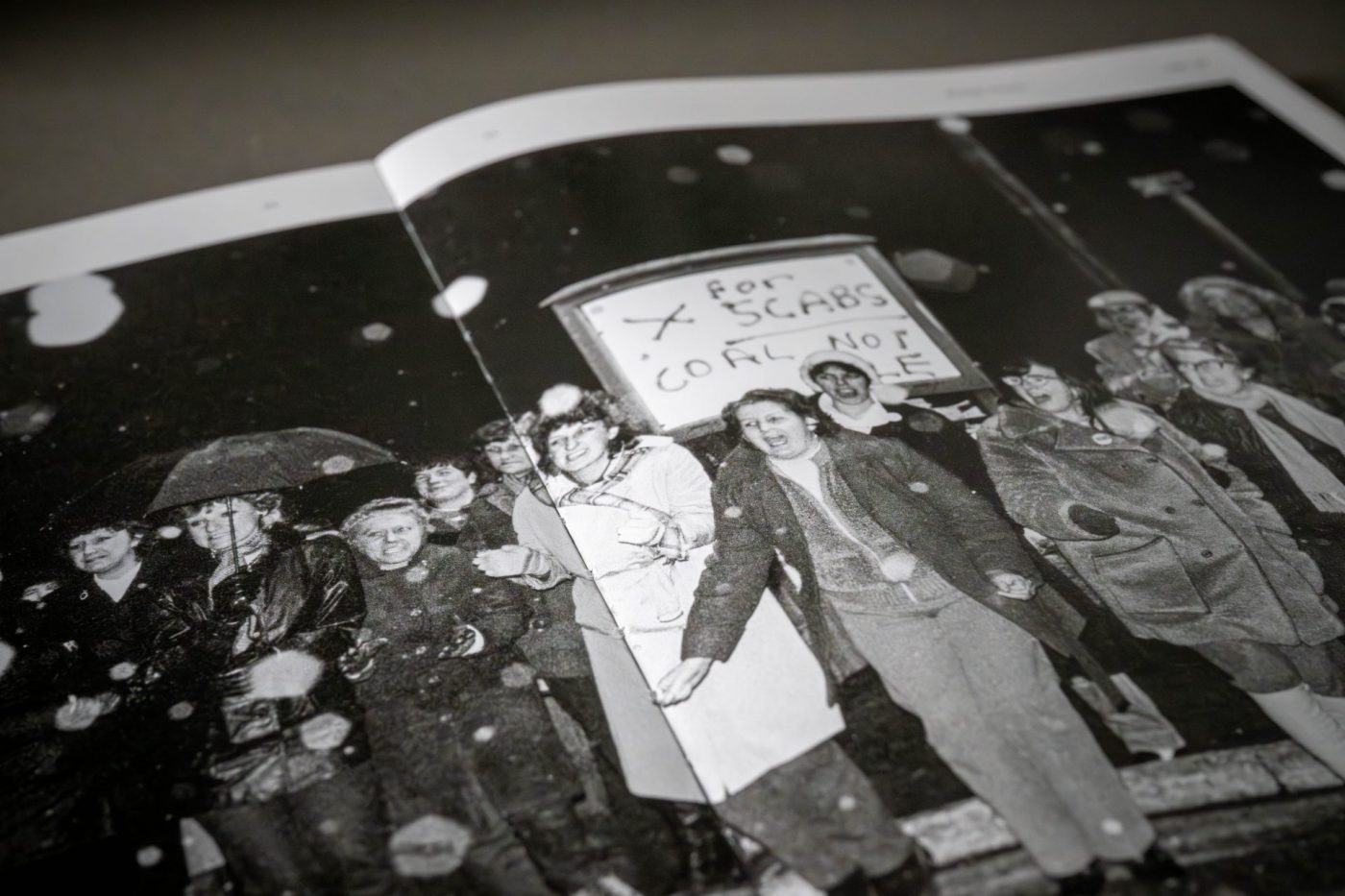

Before a photographer can develop their own vision, they need to understand how to truly see. That’s where looking at others’ work becomes indispensable. Studying the photographs of legends like Don McCullin—whose haunting, high-contrast images from war zones and inner-city Britain shaped generations—reveals the power of choice: composition, proximity, tone, and moment. When you look at an image like McCullin’s portrait of a shell-shocked soldier in Vietnam or his documentation of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, you’re witnessing not just history, but visual storytelling in its most visceral form.

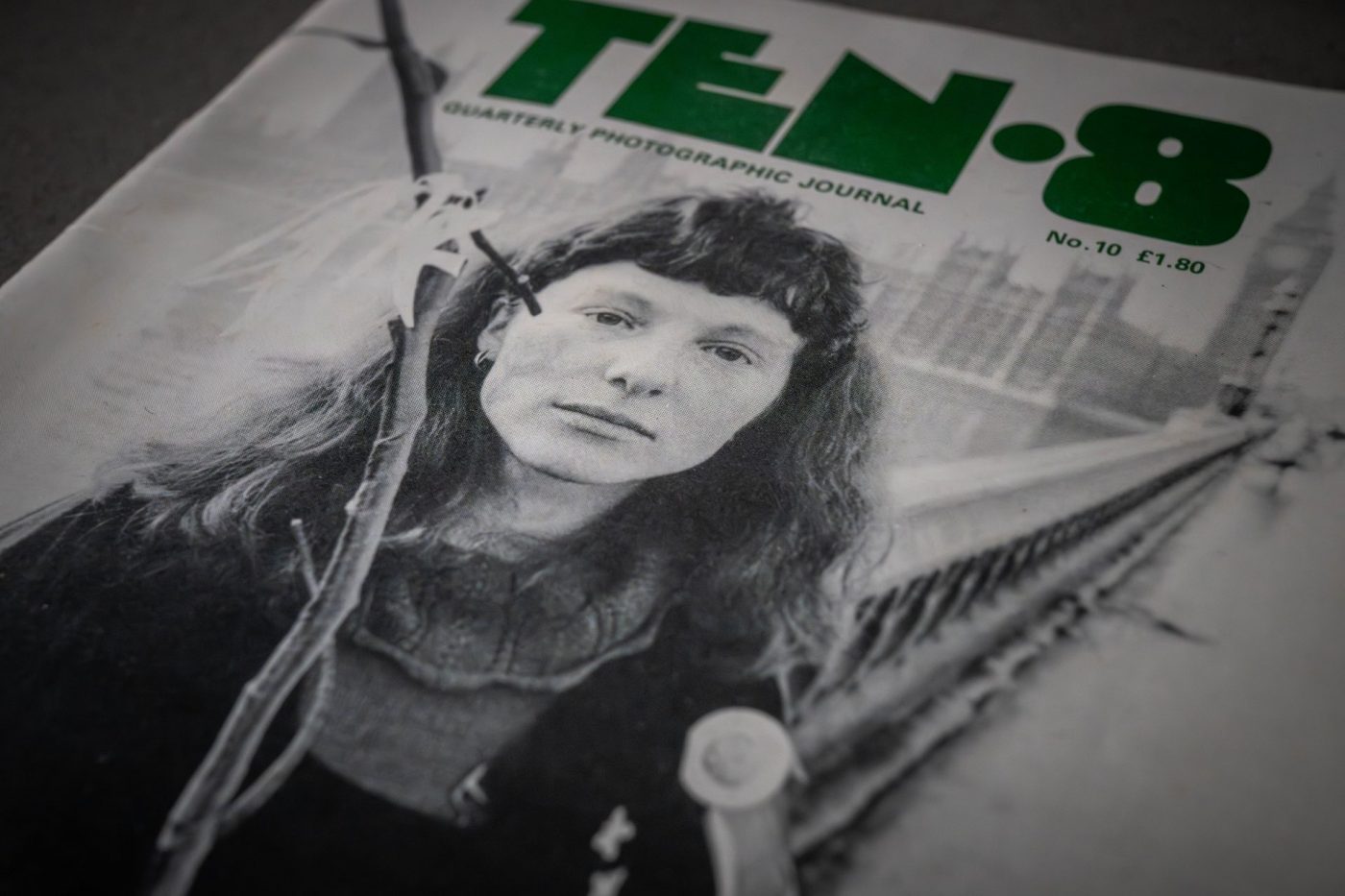

Why Books and Exhibitions Still Matter

In the digital age, it’s tempting to let your visual diet consist solely of Instagram posts or quick online portfolios. But nothing compares to the depth of engagement you get from a printed book or physical exhibition.

Photographers as Storytellers and Witnesses

One of the most important reasons to study photographers like McCullin, Susan Meiselas, or Chris Steele-Perkins is that they remind us photography is not just about visual appeal—it’s also about ethics, empathy, and responsibility.

McCullin has spoken openly about the toll of photographing war, the feeling of helplessness behind the camera, and the moral questions raised by documenting trauma. why and how.

Getting Inspired Without Copying

Many photographers start mimicking styles they admire. It’s a natural and necessary part of learning. But staying in that place can stall your growth. Studying great photographers should be like learning a new language: the goal isn’t to speak with someone else’s accent forever, but to express yourself clearly and confidently in your own words.

Look at McCullin’s use of shadow, or Nachtwey’s timing, or Meiselas’ narrative structures—but then ask yourself:

- What stories do I care about?

- What kinds of moments speak to me?

- What does my environment offer that theirs didn’t?

The strongest photographers aren’t those who imitate best—but those who use influence to sharpen their own voice.

Sharpening Your Eye (and Your Edit)

Looking at others’ work helps you understand what makes a photograph work. The more you see, the more you notice subtleties—gesture, composition, emotional timing. That clarity transfers to your own work, especially during the editing process.

Photographers who regularly consume good photography tend to become better editors. They recognise when an image is strong because it tells a story, not just because it’s technically “correct.” This awareness is something no gear upgrade can provide.

Try studying a whole photo series by a documentary photographer and note which images have been left in—and imagine what might’ve been left out. Editing, after all, is where the story takes shape.

Community, Courage, and Connection

Photography is often a solo activity—but engaging with the work of others reminds you that you’re not doing this alone. The struggles, doubts, and breakthroughs you face are the same ones faced by photographers decades ago.

When you read about how Meiselas embedded herself within communities during times of conflict or how McCullin questioned the impact of his own images, you begin to realise that the act of making photographs is always layered—with emotion, conflict, uncertainty and resolve.

Photography books and exhibitions offer more than aesthetic inspiration—they offer perspective. They remind you that your voice matters, and that you’re part of something bigger.

Final Thoughts: Look, Learn, and Then Look Within

Absorbing the work of others helps you understand what’s come before, what’s possible, and what’s at stake. But the end goal is not to become a version of someone else—it’s to find a version of yourself, made richer through what you’ve seen and studied.

So go to the exhibitions. Read the photobooks. Dig into archives. Let others’ work inspire you—but then step away from the mimicry. Look through your own lens. Tell the stories that matter to you.

Because while photography begins with seeing, the images that stay with us—the ones that make us stop and feel—are the ones where someone dared to see differently.